So many of the stories I read are about desperation. The Act of July 14, 1862 was, above all, in recognition of the fact that widows, mothers, and children of slain soldiers literally had no way of supporting themselves. In many states women could not own property, and sometimes lost custody of their children. Mothers who were already in tenuous positions depending on their sons (either having been widowed or having disabled husbands) lost, in many cases, their last hope of support.

Through our 21st century eyes, it is shocking what these women and children would do to get their $8 a month. It seems to me an almost herculean effort just to have gotten all the correct documentation to the pension office. Consider that many soldiers were recent immigrants to America. How could their widows be expected to prove legal marriage when they were married in Bavaria in the 1840s? The officiating priest might be long dead, and all the witnesses to the ceremony could still be in Bavaria or could have scattered across the globe in the age of mass immigration. I have even seen the files of widows who were still in Europe-- most often Ireland, Denmark, and Germany-- when their husbands died fighting for the Union. How's that for the land of opportunity?

In light of the desperate situation these women were thrown into, it is no surprise that many, many, many files I see are of widows who eventually lost or came close to losing their pensions because of "adulterous immoral behavior." More often, this simply means that the woman ended up living with a man she did not marry, in order that he might support her but that she could still collect her pension. Sometimes, though, this indicates that the woman had to turn to prostitution. We also see many files with letters of complaint from neighbors, revealing that the woman had become an alcoholic and was not taking proper care of her children. But having lost her husband and her only means of support in a world that had virtually no public place for women-- can you blame her?

Last week, I came across a particularly striking act of desperation. In October of 1865, Sarah Richards wrote a letter to President Andrew Johnson begging for her pension. The process of receiving her certificate was a slow one, and she was barely surviving in the waiting period. Her language in the letter in particular is strikingly elegant and pleading. Consider this: how desperate would you have to be to sit down and write a letter to the President? The letter was too faded to scan, but see the transcript below:

North Troy, Oct 18th/65

Mr. President/Honorable Sir,

Poverty sometimes drives people to desperation-- although it may not be considered a desperate act in writing to you-- yet under almost any other circumstances I should not presume or attempt to force this illiterate communication upon you. I have written once before and now again and

in the name of the Lord through whose dispensations I have been deprived of a kind companion and left a widow. I appeal to you as one who sympathizes with and feels for the interests of the widows and orphans of one land made so through one common cause. And now my dear Sir-- it is useless to multiply words-- and you will pardon me if I thereby trespass upon your patience-- what I want to say it this--

will you for the sake of suffering humanity endeavor to hurry on my pension? That is if I am entitled to it-- and I am, am I not? Does it many any difference as long as my husband contracted his disease while doing his duty whether he died out of service or in it was chronic diarrhea and he lived only 5 weeks after coming home. He never asked for his dischrage and did not know that he was for several days after the doctor marked him down. Then as he felt impressed that he could not survive long he felt an anxiety to die in his own home and native land. My attorney C.M. Lander has collected many pensions, and he says he has got those whose cases are precisely like mine-- and he gives me great encouragement. But Oh-- you don't know how much I need it. I am not able to do anything of consequence towards a living-- have been teaching school, but now my health is so feeble that I cannot do that-- and I am depending from day to day upon the charity and sympathy of the public. Although I feel thankful for their favors-- yet I suffer for many comforts which I could have if I had the means in my own hands. Oh, well you help me get it immediately-- and the widows God will help you. I am sitting in my room tonight and although cold enough for a grand fire-- I have none-- no wood or money to buy it with. I have got to go out in the morning feeble as I am and try to raise some somewhere and where to go I know not it is not time for the city to give out coal and wood to the poor, and my neighbors and acquaintances have helped me so much. I have not the (illegible) to ask them for more

and thus I live from day to day, trusting, trusting, hoping, praying, looking forward to better and brighter days-- but Oh if my (illegible) should all perish-- then what. Why God only knows what poor lonely (illegible) we would be tempted to do. I know I am poor and humble-- perhaps-- unworthy of your notice--

but the efforts on my behalf will be rewarded by One who ever pleads the case of the poor.

Yours respectfully,

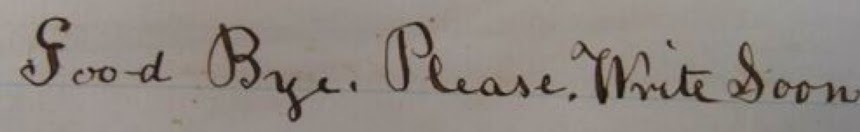

Mrs. S Richards

(WC 58842, Horace G Richards, Co C, 169 New York Infantry)

God, they just wrote better back then, didn't they? Sarah's letter might sound melodramatic, but when you consider the times you have to believe that her situation was indeed every bit as desperate as she writes it to be. All too many letters I see echo Sarah's frustration. It becomes easy to demonize pension agents when we read heart-wrenching letters like these (or, in my case, when it's clear that the pension agent was in fact an ADHD 3rd grader with a glue stick. Beside the point.). We have to remember, of course, that pension agents were just doing their job-- there were certain proofs that had to be furnished, and all we can hope is that if they were slow in approving pensions, it was only because they were so thorough. But in the meantime, Sarah paints a melancholy portrait of the many widows, mothers, and orphans who, like her, only got colder and hungrier while they waited for the pensions to be approved.